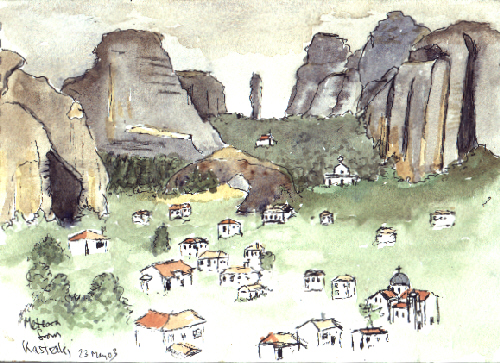

| Today six monasteries and convents

are occupied but only two of these are primarily

religious houses, Ayos Stefanos and Aya Triada

(Holy Trinity), the others are essentially tourist sites.

We should have time to visit three of these - probably

the Grand Metoron, Varlaam and Ay Stefnos.

The first monastery on the

hill up from Kastrki is Ayos Nikalaos, a small

monastery established in the 14th century. with superb

paintings by Theophanos in the 16th century

church. Because of the rock shape this monastery faces

due north rather than the usual east.

Further

up and round many bends is the tiny convent of Roussanou,or

Aya Barbara built in the 14th century with its walls

taken to the edge of the rock on all sides! Originally it

would have been occupied by monks as no women were

allowed in the Metora. The chapel has some gruesome 16th

century paintings. We get a lovely view of the convent on

our way back down.

Up

more winding road, the view ever more breathtaking, we

come to a junction. The left turn takes us to the two

biggest (and busiest) monasteries. The first of these, on

a 373 metre peak, is Varlaam which is

reached today by a footbridge and 150 steps, there

are remains of the vrizoni or winch

tower which until the 1920's was the only access.

The

monastery was built on the site of the hermitage of Ay.

Varlam in 1517 by two wealthy brothers from

Ionnina who came here soon after Athansios. Legend has it

that it took 22 years to gather the material for the katholikn

and only 20 days to build it in 1542!

In

the katholikn are painted beams and superb frescoes

from 1548, by Frango Kastellano, including in the narthex

the Last Judgement, the Life of John the

Baptist and in the domes the Ascension and a Pantokrator

In

the refectory are fabulous gold embroidered vestmentsand

a Gospel dating from 960, and in the storeroom is

a wine press and an enormous barrel, two metres diameter,

which can hold 12,000 litres.

Going

on from Varlam we come to the Grand Meteoron (the

Transfiguration)), the highest of all at 615 metres above

sea level; we climb 115 steps down and 220 up to

enter the monastery, passing on the way the cave

where Athansios lived. Access to the monastery was by rope

and net and we can see it still hanging from the vrizonitower;

today it is used only for supplies, not people, and

the mechanism is electric. There is also a bucket on a

cable slung across the chasm also used for supplies.

There is a stunning view of Varlam from here.

The

katholikon is particularly fine, some say the

finest in the Meteora; based on the churches of Mount

Athos it is a cross-in-square, with a lofty dome

supported by columns and beams, originally built in 1383

and enlarged in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Athansios

and Joasph are buried in the narthex. The

iconostasis has some superb icons. The

16th century frescoes, probably by Theophanos, depict

grisly martyrdoms. Also decidedly grisly is the display

of skulls in the ossuary! We can also visit the

vaulted refectory where there are more icons and the domed

kitchens which are arranged as if they had just

been left; there are two huge barrels here.

If

we now turn back and go straight on at the junction we

will come to two more monasteries. First is Ayias

Triados (Holy Trinity) where according to legend it

took 70 years to get all the materials to the site. Here

again there is a winching system, access today is

via 130 steps and a tunnel. The monastery, which was

built in 1438, was restored in the 1980's. There are

magnificent frescoes in the katholikon and some

splendid icons. Four monks still live here.

The

last monastery is Ay. Stefanos which we reach now

by a narrow stone bridge which crosses the ravine. There

are no steps! The nuns who live here will offer you

skirts and wraps to cover bare legs or trousers, and try

to sell you souvenirs. The monastery was built in the

late 15th century on the site of a 12th century

hermitage. The refectory, which has brick domes,

is now a museum with lovely embroidered vestments (C18/19th),

altar silver, an ebony and ivory bishop's throne,

C17/18th icons and a 6th century manuscript, and

others from the 10th - 17th centuries; there is also a dictionary

from 1499. The frescoes in the 18th century church

are newly restored; those in the 15th century chapel are

badly damaged. Last year these were being restored. There

is a pretty rose garden with box hedges and a superb view

over the plain and Kalambaka. Down the steps in the

garden are loos a la Turque!

|